Finding roots with Newton's method

This is not a math tutorial. See Why am I writing about math?

The root, or zero of a function is any input value that makes the function’s output equal to zero, i.e., . Roots are the points where the function’s graph crosses or touches the horizontal x-axis.

What is Newton’s Method? #

Following this video, for no particular reason (haven’t watched it yet. Edit, it turned out to be too fast for me.):

-

pick an x close to the root of a continuous function

-

take the derivative of to get

-

plug those values into this formula:

-

repeat until the result converges, i.e., where

Example, find the root of:

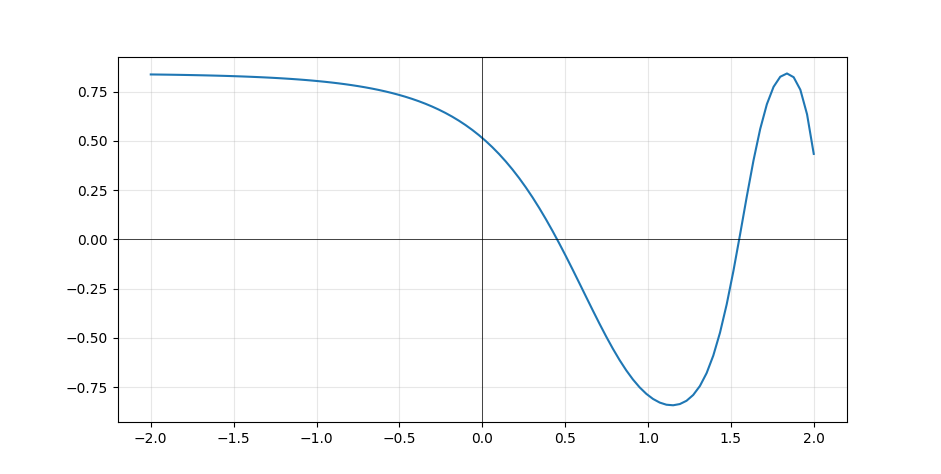

Let’s make it real with Python:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def sin_cos_exp(x):

return np.sin(np.cos(np.exp(x)))

x_arr = np.linspace(-2, 2, 100)

y_arr = [sin_cos_exp(x) for x in x_arr]

plt.plot(x_arr, y_arr)

plt.axhline(y=0, color="k", linewidth=0.5)

plt.axvline(x=0, color="k", linewidth=0.5)

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.show()

sin(cos(e^x))

The graph is showing that the function will return a value of 0 when it’s called with values that are approximately 0.4 and 1.5. Newton’s method can be used to find a root (an argument that will cause the function to cross or touch the 0 line), by repeatedly calling:

x_next = x_current - (f(x_current) / f'(x_current))

Where x_current is the value that was previously assigned to x_next. Note that I’m using f'(x_current) to mean

the derivative of the function with respect to x_current.

For my own reference, this can be made clearer with Python code:

import numpy as np

def sin_cos_exp(x):

return np.sin(np.cos(np.exp(x)))

# finding the derivative of f(x) = sin(cos(e^x))

# Note that:

# d/dx[sin(x)] = cos(x)

# d/dx[cos(x)] = -sin(x)

# d/dx[e^x] = e^x

# think of it as three nested functions:

# sin(u) where u = cos(e^x); d/dx[sin(cos(e^x))] = cos(cos(e^x)) x d/dx[cos(e^x)]

# cos(v) where v = e^x; d/dx[cos(e^x)] = -sin(e^x) x d/dx[e^x]

# innermost e^x; d/dx[e^x] = e^x; (the derivative of e^x is e^x)

# f'(x) = cos(cos(e^x)) x -sin(e^x) x e^x

def sin_cos_exp_derivatives(x):

expx = np.exp(x)

return np.cos(np.cos(expx)) * -np.sin(expx) * expx

print("x=0.0", sin_cos_exp_derivatives(0.0))

# x=0.0 -0.7216061490634433

print("x=0.4", sin_cos_exp_derivatives(0.4))

# x=0.4 -1.4825498531537413

With the sin_cos_exp and sin_cos_exp_derivatives functions, it’s possible to write a

newtons_method function:

def newtons_method(x0, tolerance=1e-6, max_iter=100):

xn = x0

for n in range(max_iter):

fxn = sin_cos_exp(xn)

if abs(fxn) < tolerance:

print(f"Found solution {xn} after {n} iterations.")

return xn

dfxn = sin_cos_exp_derivatives(xn)

if dfxn == 0:

print("Zero derivative. No solution found.")

return None

xn = xn - fxn / dfxn

print("Exceeded max iterations. No solution found.")

return None

newtons_method(0.4)

newtons_method(1.5)

Calling that function returns:

Found solution 0.45158270529021377 after 3 iterations.

Found solution 1.5501949939676198 after 3 iterations.

Since it’s a periodic function, there are an infinite number of zero crossings:

{{x< figure src="/images/sin_cos_exp_periods.png" >}}

Finding square roots via Newton’s Method #

Find the zero for:

Where a is the value we want to get the square root of.

Confirm that makes sense:

The reasoning is that when f(x) = 0 then x^2 = a and x = sqrt(a)

The derivative of f(x) = x^2 is:

Having the derivative, plug the formulas into:

This can be simplified to (NO, IT CAN’T! Be careful about Youtube math tutorials, it should be + a, not - a):

Newton’s formula can be simplified to:1

The simplification isn’t obvious to me. I’ll work it out below, using x instead of x_n to

clarify what’s going on:

Starting from:

Multiply x by 2x/2x (essentially 1) to express everything with a common denominator:

Simplify to:

Combine the fractions:

Simplifies to:

This can be expressed as:

The first term can be simplified, giving:

Then factor out the 1/2:

Using x_n instead, so that it’s expressed in the correct form for Newton’s method:

Intuitive explanation of Newton’s Method for square roots #

Multiplying (x_n + a/x_n) by 1/2 is the same as calculating the average of x_n and a/x_n.

If x_n is too big, then a/x_n will be too small (less than the square root of a), and the

average of x_n and a/x_n will be closer to the square root of a. And vice versa.

Python demo:

In [22]: a = 9

In [23]: x = 1

In [24]: x = 0.5 * (x + a/x)

In [25]: x

Out[25]: 5.0

In [26]: x = 0.5 * (x + a/x)

In [27]: x

Out[27]: 3.4

In [28]: x = 0.5 * (x + a/x)

In [29]: x

Out[29]: 3.023529411764706

In [30]: x = 0.5 * (x + a/x)

In [31]: x

Out[31]: 3.00009155413138

Calculating the square root of 2 from an initial estimate of 1:

In [32]: a = 2

In [33]: x = 1

In [34]: x = 0.5 * (x + a/x)

In [35]: x

Out[35]: 1.5

In [36]: x = 0.5 * (x + a/x)

In [37]: x

Out[37]: 1.4166666666666665

In [38]: x = 0.5 * (x + a/x)

In [39]: x

Out[39]: 1.4142156862745097

In [40]: x = 0.5 * (x + a/x)

In [41]: x

Out[41]: 1.4142135623746899

In [42]: x = 0.5 * (x + a/x)

In [43]: x

Out[43]: 1.414213562373095

References #

Johnson, S. G. “Square Roots via Newton’s Method”. MIT Course 18.335. https://math.mit.edu/~stevenj/18.335/newton-sqrt.pdf .

Notes #

-

S. G. Johnson, “Square Roots via Newton’s Method”, MIT Course 18.3335, February 4, 2015, p.1, https://math.mit.edu/~stevenj/18.335/newton-sqrt.pdf ↩︎